With one result being that there is now quite a lot of evidence that music can both express and engender the basic emotions – say anger, fear, happiness, sadness, love/tenderness – and that the way that it does this is not that unlike the way that voice can express the same basic emotions. Faces are quite good at this too, although the means used there are, naturally, quite different.

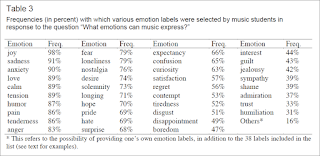

The table above addresses the ‘what emotions’ question and was compiled from the responses to a survey of 135 music students, 69 men and 66 women, mostly in their twenties and who came from four different music conservatories in three European countries. Mostly, but by no means all, students of the western classical tradition. An impression of what a sample of musical others think what music can do. A survey which was reported in 2003 at reference 1.

What follows are some speculations arising from this thought that there is some special link between music and emotion, much stronger for most people than that between, for example, paintings and emotion or buildings and emotion.

My attempt at the labels in the table

For my purposes, I exclude vocal music, choral music and opera, where there is likely to be vocal and plenty of other non-musical priming for emotions. I also exclude music which is being performed in a supporting role to some other event, like a tea-dance, a battle or a funeral. I do not think that the surveyors did this.

I go along with joy, sadness, calm, tension and humour – half of the first column.

I would have given a higher rating to fear, solemnity, expectancy, confusion and satisfaction.

I would have thought it hard to discriminate between anger, pain and hate. All rather intense, jangling and loud experiences.

At which point, I stuck. I found it hard to see how one could go much further. So overall, I think there are too many words, that the table suggests that these students regard music as having a far greater range (or reach) and a far greater discrimination than I think likely. Although there is a procedural problem here in that the students were prompted with the list. How different would the result have been if there had been no prompts? Or if the prompts had been expressed in terms of the circle of emotions which follows below?

Not without reason, to my mind, that most work in this area sticks with less than half a dozen emotions.

Aesthetics

Then music is, has certainly become over the millennia that it has been around, more than a device for engendering emotions of the ordinary sort, which can be engendered otherwise. As a sophisticated art form, it can engender emotions (feeling might be a better, less loaded word) of its own. One’s appreciation of some music has little to do with the wider world and is not usefully reduced to the emotions appropriate to our dealings with each other, with that wider world.

Which suggests the idea of overlap. There are some emotions which arise in the ordinary way and which can be engendered by music. There are some which cannot be so engendered; perhaps amplified but not engendered. And there are some emotions which arise from music which are peculiar to music and which do not arise in the ordinary way. I associate to the overlapping discs of the Venn diagrams described at reference 5.

The two dimensions theory

Many workers have come to the view that emotions can be mapped in an attractive and informative way onto a two dimensional plot, where one dimension is about valence, whether the feeling is pleasant or unpleasant and the other is about arousal, whether the feeling is strong and intense or flat and dull. With both dimensions often being shown, conventionally, as running from minus one to plus one. With the emotions sometimes placed on something like a circle. Sometimes called the circumplex theory of affect, for which see reference 10.

Notice the slight awkwardness in that valence naturally maps onto the range minus one to plus one, while arousal maps naturally onto the range zero to plus one. Arousal does not do negative. A lack of symmetry here, which can be fixed by allowing arousal to vary about its waking mean, rather than upwards from zero.

Some go so far as to say that there is a one to one map between emotions and position on this plot.

For myself, while I find the mapping convincing in general terms, I would not go that far. I do not believe that the whole content of emotions, the whole range of feeling, is captured in just two dimensions. The two dimensions do indeed help in a general way, but one should not try to get too much from them.

Others tell us that to get from a two dimensional emotion to a real emotion requires culture, language and computation. We are trained to feel complex emotions like pride and shame. And different cultures will do these things in different ways.

I have not come across anyone trying to do the same sort of thing for music, although thinking with my fingers, one dimension of happy to sad and another dimension of excited and fast to solemn and slow does not sound too improbable.

Other bits of theory and speculation

Humphrey talks at reference 6 of feelings, emotions and ultimately consciousness being internalised versions of afferent motor commands, be those commands be to do with the eyes, the ears or some other part of the body, inside or outside.

Schnupp and Nelken talk at reference 7 of chunks of sound having what we call pitch, important in the music of most cultures, when they have period, when they repeat. When those chunks repeat enough times, at frequencies in the range (say) 40Hz to 4,000Hz, we experience pitch. Remembering here the rather different fact that natural chunks of sound rarely come with just one frequency in their spectra.

Pandarinath and his colleagues talk at reference 8 of non-rhythmic movements in arms coming with rhythmic oscillations in the brain. At least if you look at the brain in the right sort of way.

Buzsáki puts rhythm into the title of his book about brain waves at reference 9. But, to be fair, it is hard to have waves without rhythm.

With my point here being that a lot of brain activity seems to involve oscillations, repetition or rhythm.

My heart filled with pride

We sometimes talk of our hearts filling with pride, or perhaps just filling with pride. The title of the paper at reference 1 starts ‘expressivity comes from within your soul’. In which the music is perhaps an enabler rather than a determiner. The music can open up the soul to emotional experience, strip away much of the conscious overlay, perhaps give that experience the valence and arousal of the two dimensional mapping we talked about above, but it needs something else to provide finer discrimination. And this might be the role of the title of the piece of music, the context in which it is usually played or the words which are part of it.

An opening up which makes room for what I think is an important category: music which makes one feel very emotional, but in a way which does not have valence, an emotion which was talked about at reference 2. It is not good or bad, neither is it about anything in the way of the labels offered in the course of the survey talked about above.

A rather different example would be the French drum beat called the ‘pas de charge’ (hear reference 3), which is exciting, but which only acquires its full emotional charge in the context of a great mass of soldiers advancing to attack. Note that the charge is positive in the case of the attacking soldiers, negative in that of the attacked; it all depends on the point of view, not just on the music itself. Apparently Napoleon knew all about the ability of music to terrify the enemy, by which point the battle was more or less won. All well-evoked, in words, by the book at reference 4.

The trumpet calls of cavalry are different again. Here the calls are of short duration and are more by way of signals or commands than pieces of music. Bright and loud, but they acquires the detail of their emotional colour from context and by association.

The famous funeral march of Chopin, that is to say the outer sections of the third movement of his Piano Sonata No. 2 in B♭ minor, Op. 35, is perhaps a similar case to the ‘pas de charge’, even though the slow, sombre beat of the opening is less ambiguous than this last. And not facing two ways at all. Nevertheless, the fact that something, or that part of something, might be very suitable for a funeral, does not mean that it was necessarily written for a funeral, or that it cannot be put to other uses.

Mood music

First, we have the music played by builders – both tradesmen and their labourers – on their transistor radios when doing maintenance work in or on houses. I suspect part of this is asserting their right to do this, while knowing, or perhaps because they know, full well that many customers find it irritating, to say the least. But it does also seem to fulfil some need.

Second, we have the music played in some public places, perhaps the breakfast room in a hotel, the purpose of which is mainly to fill the otherwise uncomfortable void and to give guests a little privacy. Emotional content very low.

Third, we have the music played in establishments like shops, the purpose of which is to get you going. To get you moving around the store at a reasonable clip and to get you spending. At least that is the idea – with a lot of people just being annoyed. Perhaps just spraying extra oxygen into the air is better. Nevertheless, this sort of music does has an effect on customers, it does change their moods, at least on average. It is effective, not so say affective.

Fourth, we have the music which management used to use to improve the performance of their teams. Perhaps sailors working the capstan on a ship-of-the-line or soldiers on a gruelling route march. The music is chosen to encourage the motor action to synchronise with the musical action, synchronisation which helps the sailors and soldiers keep it up for longer than might otherwise be the case. Maybe it counts as cheating if you try this in a rowing race.

Fifth, we have mood music proper. So the tea room of a smart hotel might sport a harpist or a trio to play light classical music. The purpose of which is partly to provide privacy, partly to impress but also to set the tone. To get people into the right frame of mind to enjoy their tea and the conversation (or whatever) which goes with it. Or the host at a party might select the music which she thinks that her guests will like and which she also thinks will get them in the right mood for the sort of party she has in mind. And this might be as much to do with the order of the play list as the individual items. No doubt disc jockeys in clubs think along the same sort of lines. In my youth, the last few dances at a dance were carefully chosen to encourage a bit of close contact and snogging; the grand finale as it were.

With a rather gruesome variety of mood music being the drum rolls which used to be used to accompany military punishments and executions. Which is also another example of the disconnect between the emotions engendered in the various participants – musicians, victims, executioners and audience – we had with the ‘pas de charge’.

In nearly all these cases, the intention of the person choosing the music is to engender emotions and feelings. Part of this engendering is the signalling function of the music. Everyone knew what the last dances were for. Another part is the context: everyone knew about last dances at dances. But another part is fit. The music, while probably not forcing the desired response of itself, has to encompass it, is intended to facilitate it.

Conclusions

There is no doubt that some people can get very emotional when listening to music. But it is not at all clear to me that these emotions are well described by the sort of labels illustrated above, or that music has anything like that specificity in the emotions it generates.

It seems more likely to me that the music itself is just one part of the package. Other parts of the package include:

- The words, if any, which go with the music

- The context in which the music is being played, for example profane or sacred, in concert or at home

- The role of the person concerned in that context

- The state of mind of the person concerned

- How well that person knows the piece of music concerned. Or perhaps just the work of the composer in general, or works of some particular sort in general. Perhaps this person knows all about madrigals and that person knows all about string quartets.

So any physiological linkage between music and emotion – with the expression of sound in the brain, the mapping of sound from the ears to the interior of the brain where, as well as emotion, it generates efferent output doing stuff to the body – is going to have to be fairly flexible in its workings, and for this reason some writers talk of the brain totting up the various cues and contributions in coming to its decision. And I do think it likely that there is some physiological linkage of this sort. Maybe something to do with the evolutionary function of vocal communication of emotion, before the invention of speech proper.

Then, we have the Venn diagrams mentioned above. Some of the emotions arising from listening to music do not crop up in the real world, except in so far as they crop up in contemplation of some other art form or artefact, some of the emotions arising in the real world do not crop up in music, except in so far as it nicely accompanies emotions cued or engendered by other means, and some emotions really do live in both worlds.

And lastly, we have the idea of enablement. We suppose that music establishes some kind of repetitive activity in the brain, oscillations in some state space in the brain, under which umbrella it is easy for the repetitive activity, the oscillations expressing emotions to thrive. The music and the emotions are in some kind of symbiosis, a symbiosis along the same lines as that between music and working the capstan, mentioned above. This idea of enablement being one of my own favourites and about which I hope to be able to say more in the not too distant future.

References

Reference 1: Expressivity comes from within your soul: A questionnaire study of music students’ perspectives on expressivity - Lindström, E., Juslin, P. N., Bresin, R., & Williamon, A. – 2003.

Reference 2: http://psmv3.blogspot.co.uk/2016/06/a-feeling-without-name.html.

Reference 3: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sXwDI6HW2Sw. I can’t find a drums only version, but this gives the general idea of the ‘pas de charge’.

Reference 4: Of living valour: the story of the soldiers of Waterloo – Barney White Spunner – 2015.

Reference 5: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Venn_diagram.

Reference 6: Seeing red - a study in consciousness - Humphrey - 2006.

Reference 7: Auditory Neuroscience: Making Sense of Sound - Jan Schnupp and Israel Nelken – 2012.

Reference 8: Neural population dynamics in human motor cortex during movements in people with ALS - Chethan Pandarinath, Vikash Gilja, Christine H Blabe, Paul Nuyujukian and others – 2015.

Reference 9: Rhythms of the brain - György Buzsáki – 2011.

Reference 10: The circumplex model of affect: An integrative approach to affective neuroscience, cognitive development, and psychopathology - Jonathan Posner and others – 2005.

Group search key: srd.

No comments:

Post a Comment